Seton Hill Assistant Professor Brett Aiello Co-Authors Study Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

It took longer than the blink of an eye, but a research study led by Seton Hill University assistant professor of biology Brett Aiello and his former graduate school colleague Thomas Stewart, assistant professor of biology at Penn State University, has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study reveals clues as to how the ancestors of humans and other tetrapods - the group of animals that includes mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians - evolved an adaptation for life on land.

The researchers looked at the mudskipper, a blinking fish that has independently evolved an amphibious lifestyle, much like the earliest tetrapods, and spends much of its time out of the water. They show that these fish have also evolved a blinking behavior that serves many of the purposes of human blinking, and, as such, provides clues into the traits that evolved to allow tetrapods to transition from water to life on land some 375 million years ago.

While Aiello’s work being published is important, it’s the process that he finds the most rewarding.

"Intellectual curiosity and discovering new things with incredible colleagues and students continues to sustain me in this work.”

“When you go back and reflect on a career, there are definitely those moments you will find where you were able to break through and make a difference, and I feel as though this is going to be one of those moments,” Aiello said. “But what I’m going to remember the most about this experience is the relationships developed with colleagues and, I hope, the impactful work with students. Intellectual curiosity and discovering new things with incredible colleagues and students continues to sustain me in this work.”

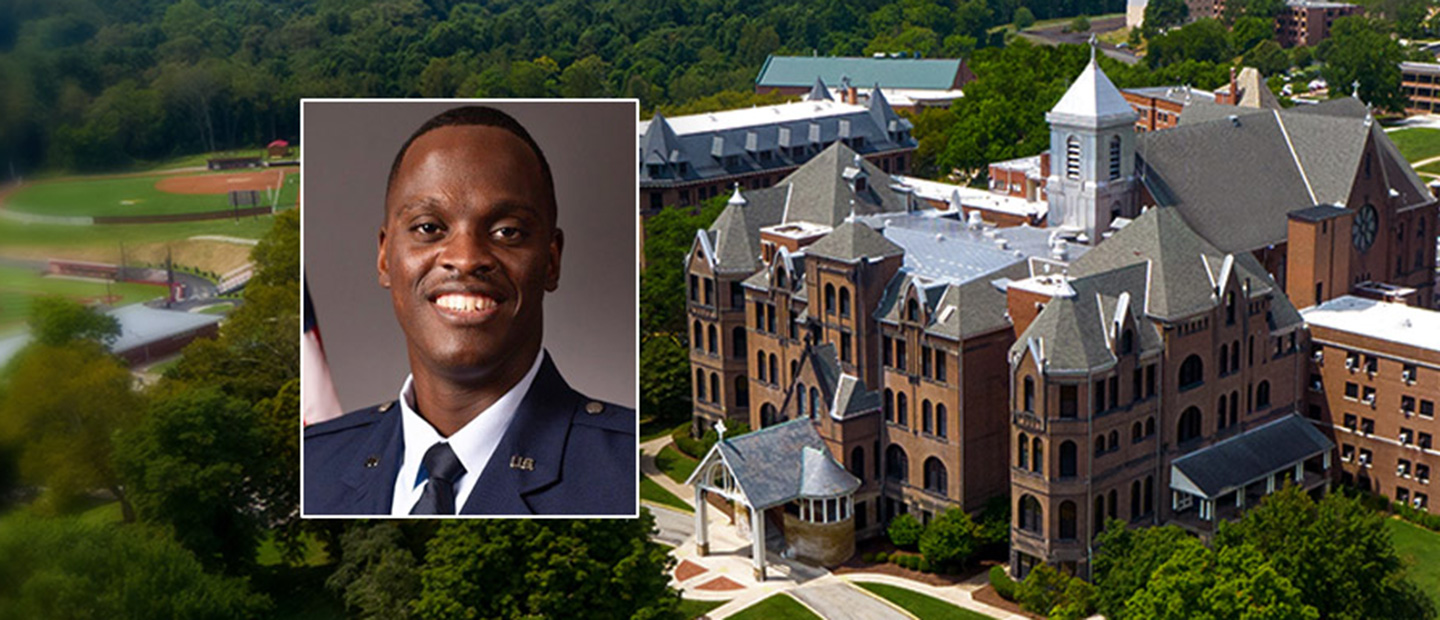

Aiello joined Seton Hill’s faculty in Fall 2022. While his mudskipper research was conducted elsewhere, his writing occurred while at Seton Hill - and he has already begun working with Seton Hill undergraduates on research projects.

“All of us at Seton Hill congratulate Dr. Aiello on being published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and this achievement reflects on the caliber of faculty we have at the university,” said Seton Hill Provost Susan Yochum, SC, Ph.D. “Brett is a hands-on educator who engages undergraduates with his natural curiosity and his enthusiasm for scientific research, and I know our students are already benefiting from his ongoing research.”

Aiello, a native of Youngstown, Ohio, earned his undergraduate degree in zoology from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio; his master’s degree in biological sciences from Youngstown State University; and his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, where, he said, he began to recognize the importance of major transitions in the history of animals.

Aiello conducted post-doctoral work in a physics lab at Georgia Tech where he brought techniques from that discipline - which is heavy in math - in order to apply them to uncover new and creative ways to answer biological questions. “Interdisciplinary collaborations will play a major role in the future of big, impactful science,” he said.

While at Georgia Tech Aiello was texting with Thomas Stewart, a colleague he met in graduate school at the University of Chicago. They share a profound interest in how and why animals are the way they are and, especially, on the adaptations necessary to bring vertebrates from water to land.

They began to discuss ways they could collaborate on research together, and they landed on the behavior of blinking.

“We started noticing this diversity of an under-studied behavior,” he said, noting that animals blink in a variety of ways. Some raise a lower eyelid, others use their upper eyelid. Some species have a third, clear eyelid they use to blink.

“What we found in initial investigations is that it's a really complicated behavior,” Aiello said. “Then we came across this incredibly charismatic fish - the mudskipper.”

“Blinking in mudskippers appears to have evolved through a rearrangement of existing muscles that changed their line of action and also by the evolution of a novel tissue, the dermal cup,” said Aiello.“This is a very interesting result because it shows that a very rudimentary, or basic, system can be used to conduct a complex behavior. You don’t need to evolve a lot of new stuff to evolve this new behavior — mudskippers just started using what they already had in a different way.”

Aiello and Stewart - with their research groups at Georgia Tech and the University of Chicago - found that mudskippers blink for the same reasons that humans do - to keep their eyes wet, protect from debris, and to clean their eyes.

It was also through this research project that Aiello developed his interest in teaching at the undergraduate level. At Georgia Tech, Aiello taught an authentic research course for undergraduate students, which included interdisciplinary teams of students conducting long term, sustained research projects. Students were able to keep enrolling in the course semester after semester. These undergraduate students were heavily involved in the mudskipper research project.

“We were pushing the envelope of science and learning how to build that research skill,” he said. “It made me want to be a professor at a primarily undergraduate liberal arts institution so I could continue to have that amazing interaction with budding scientists. It was the most rewarding aspect of the scientific process for me. I want to bring that same kind of experience and hopefully life-changing moments of discovery to our students here at Seton Hill.”

In addition to Aiello and Stewart, the research team includes M. Saad Bhamla, Jeff Gau, Kenji Bomar, Shashwati da Cunha, Harrison Fu, Julia Laws, Hajime Minoguchi, Manognya Sripathi, Kendra Washington, Gabriella Wong and Simon Sponberg at the Georgia Institute ofTechnology; John G.L. Morris at Westmead Hospital in Sydney, Australia; and Neil H. Shubin at the University of Chicago.